Master-mi’mar Ustad Haj Sa’ban-Ali founded the Agha Bozorg Mosque (Persian: مسجد آقا بزرگ Masjed-e Āghā Bozorg) in the late 18th century; it is a historical mosque in Kashan, Iran. It is renowned for its symmetrical architecture and appealing appearance. The complex is named after the Mulla-Mahdi Naraqi II theologian, identified as Aqa Buzurg, and an inscription dates the building from 1832 to 1833 (1248 AH). In the center of the city, there is a mosque and a theological school (madrasah). A homage to Islamic architecture, elements of Persian architecture are often delicately taken over by the mosque.

(Agha Bozorg Mosque, main building)

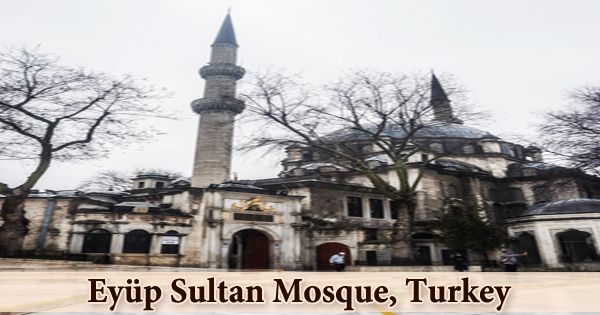

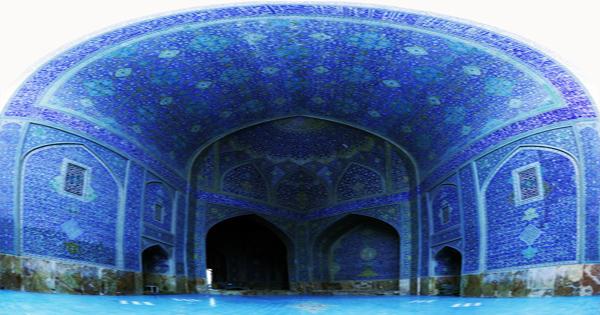

Agha Bozorgh Mosque was built for prayers, preaching, and teaching sessions conducted by Molla Mahdi Naraghi II, also known as Mulla Mohammad Naraqi, famously known by the Shah himself for his title of Āghā Bozorgh (literally meaning large or great lord). This magnificent mosque has a vibrant backyard and even an underground oasis for prayer ceremonies. Its blue and turquoise tiles, which are tactfully and beautifully arranged next to each other to form fascinating Persian geometric patterns, are undoubtedly the most eye-catching feature of this location. Another charming piece of Persian architecture can be found by tourists in the yard.

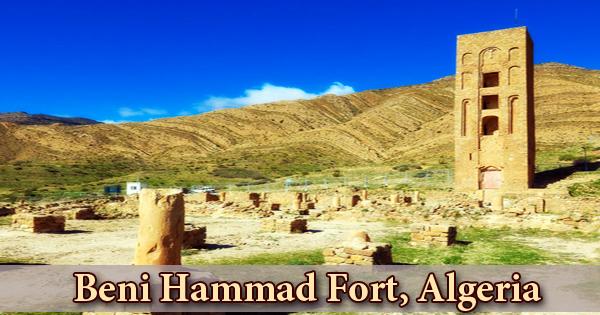

Several congregational halls, adjacent arcades, tiled minarets, large badgirs (wind towers), and an austere dome comprise the massive structure. With Quranic inscriptions and mosaics, the mud-brick walls, arches, and ceilings are also covered. A long, roughly rectangular footprint oriented northwest to southeast is filled by the house. The middle of the complex is occupied by a sunken courtyard constructed on two levels (ground floor and balcony). On the northwestern side, at the end of a high street lined with stores, is the entrance to the complex. It takes the shape of an iwan-portal, arched, domed. This portal leads from an arched aperture located directly opposite the entrance portal to a high, domed vestibule that overlooks the courtyard. Good examples of this art are the central courtyard and the lovely pool in the middle.

Mulla Ahmad Naraqi is renowned for rallying Iranian forces against the Russian invasion of northern Iran and calling the invading Russians a “jihad” or “holy war”. He was able to effectively reconquer the Iranian lands that had been taken during the offensive by the invading Russian armies. Mulla Ahmad Naraqi, his brothers, his sons, and his father, Mulla Muhammad Mahdi Naraqi, known as Muhaqqiq Naraqi, are some of the most prominent Shi’a clerics of their time, as well as some of the most famous Islamic Iranian scientists. Mulla Ahmad Naraqi and his father, Muhaqqiq Naraqi, are particularly well known and honored as the leading Islamic leaders of their time in Iran to this day.

(View of Agha Bozorg Mosque)

The mosque has been described as “the finest Islamic complex in Kashan and one of the best of the mid-19th century”. This beautiful architectural wonder is very atmospheric and wonderful throughout the day and at night, very incredible. As its courtyard is surrounded by student quarters, the interesting combination of mosque and madrassa (school) is very wonderful and well-constructed. Two archways leading to a flight of a few stairs that lead to an open roof terrace overlooking both levels of the courtyard flank this opening. There are two wide corridors on either side of these two archways (to the right and left as one enters the vestibule) that descend on-ramps and turn at right angles, leading to arched entrances at either end of the upper level of the courtyard’s northwestern facade.

The upper level of the courtyard is flanked by the above-mentioned roof terrace on the northwest side (raised by several feet above this upper level); by the façade of a monumental mosque on the southeast side; and by rows of blind niches on its two lateral sides (southwest and northeast), deep enough to sit in. This level acts as a balcony overlooking the courtyard’s sunken ground level. It consists of two wide iwans, one in front of the mihrab and the other by the entrance, noted for its symmetrical architecture. There are two minarets in the iwan in front of Mehrab with a brick dome. It was here that Ustad Ali Maryam began his architecture career as a pupil. Under the roof terrace and entrance pavilion, on the northwestern side, is a basement (sardab) consisting of a vast open space vaulted with deep arches. From this subterranean structure, flanking the entrance pavilion, wind catchers (badgir) in the form of towers rise.

There was also a religious school next to the mosque, all of which combined to create a single building. Badgir, the typical wind-catcher in Persian architecture that functioned as the building’s air-conditioner, also has this location. All these things reflect the simple lives of both the people and the Kashan rulers many years ago. The interior of the building consists of a central, octagonal chamber with a wide dome directly behind the central iwan, opening on three sides to an ambulatory surrounding it through archways on each of its eight sides. The two side arches on the facade of the main courtyard lead to the ambulatory sidearms. The outpatient’s northeastern arm opens to the small side court, while the southwestern arm opens to the shabistan, which is a rectangular space separated by twenty freestanding pillars into six aisles of five bays each. A single mihrab marks the path of prayer on the southwestern wall of the room under the southernmost bay.

In the heart of Kashan, Agha Bozorg Mosque gives tourists easy access to most of the popular tourist attractions of Kashan, Iran. This mosque is a sign of the simple lives of religious leaders and people in the past. The interesting point is that inside this mosque there are several sections that are eye-catching and appealing for taking pictures.

Information Sources: