According to a new study done by Northumbria University, contrary to popular belief, the venom of snakes and spiders is filled with germs, including bacteria that might cause illness in humans who have been bitten.

For decades, experts believed that animal venom was a completely sterile environment because it included antimicrobial substances—materials that may kill microorganisms.

However, fresh scientific evidence from a study headed by Sterghios Moschos, Associate Professor in Cellular and Molecular Sciences at Northumbria University, and venom scientist Steve Trim, Founder and CSO of biotechnology startup Venomtech, has revealed that this is not the case.

The research, which was published today in the scientific journal Microbiology Spectrum, shows how flexible microbes may be. The research shows that bacteria can not only live in the venom glands of various snake and spider species but can also evolve to resist the famously lethal liquid that is venom.

The findings also show that venomous animal bite sufferers may require infection treatment in addition to antivenom to combat the poisons delivered by the bite.

Disproving the venom sterility dogma

Dr. Moschos and colleagues analyzed the venom of five snakes and two spider species to fill a research gap. “We discovered that all of the poisonous snakes and spiders we studied contained bacterial DNA in their venom,” Dr. Moschos revealed.

“Common diagnostic methods failed to accurately detect these bacteria—if you were infected with them, a doctor would likely prescribe the wrong drugs, potentially worsening your illness.”

“We were able to clearly identify the bacteria after sequencing their DNA and discovered that they had altered to withstand the venom. This is remarkable since venom is like a cocktail of antibiotics, and it is so thick with them that you would think bacteria would have no chance. They not only had a chance, but they had already done it twice using the identical methods “Dr. Moschos stated.

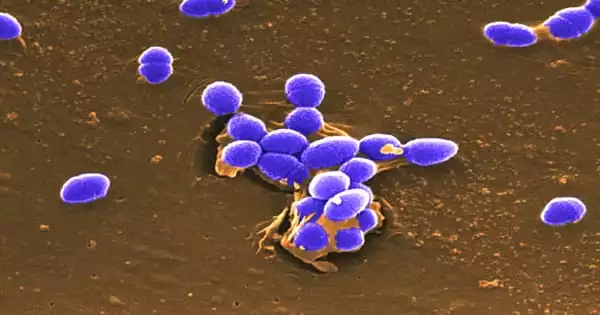

“We also directly tested the resistance of Enterococcus faecalis, one of the bacteria species found in the venom of black-necked spitting cobras, to venom itself and compared it to a classic hospital isolate: the hospital isolate did not tolerate the venom at all, but our two isolates happily grew in the highest concentrations of venom we could throw at them.”

Clinical Treatment Implications

Annually, 2.7 million poisonous bite-related injuries occur, primarily in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. It is estimated that 75% of these individuals will acquire infections in venom toxin-damaged tissue, with bacteria Enterococcus faecalis being the most prevalent cause of sickness.

These illnesses were originally assumed to be the result of having an open wound from the bite, rather than the infection-causing germs coming from the venom itself.

According to the researchers, these findings demonstrate the need for doctors to treat snakebite victims for infection as well as tissue loss as soon as feasible.

“By examining the resistance mechanisms that let these bacteria survive, we can identify totally new strategies to combat multi-drug resistance, possibly via creating antimicrobial venom peptides,” Venomtech’s Steve Trim noted.