Extreme heat waves can kill a large number of birds and animals. However, it is more typical for an animal to suffer from minor heat stress that does not kill it. Unfortunately, our recent findings show that these people may experience long-term health consequences.

The DNA of young birds can be damaged by hot and dry circumstances in their first few days of life, according to a new study released today. This can lead to their growing older, dying younger, and having fewer children.

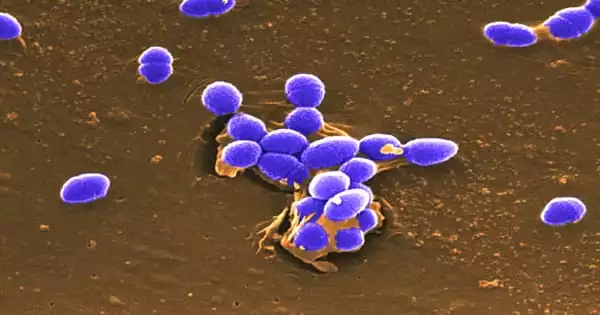

The purple-crowned fairy-wrens, a little endangered songbird from Northern Australia, were our focus.

The findings show that unless wren populations can quickly adjust to climate change, they may struggle to live as global temperatures increase. When projecting how biodiversity will fare in a warmer world, it’s critical that we evaluate such subtle and otherwise concealed influences.

The cost of growing up in the heat

Because of their immobility, fast development, and immature physiology, nestlings are particularly susceptible to high temperatures. Furthermore, the effects of heat stress may be magnified in young birds since harm may last throughout maturity.

As part of a long-term ecological research, we closely observed a population of uniquely marked purple-crowned fairy-wrens at the Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s Mornington Wildlife Sanctuary in Western Australia’s Kimberley area.

Small social groups of these insect-eating birds form around a breeding couple. The birds we studied spend their days in deep undergrowth near their favorite riverbank site, which they fiercely protect against intruders.

Breeding can take place at any time of year, although it peaks during the monsoonal rainy season. One to four nestlings are found in each nest. They encountered maximum air temperatures of 31–45°C during our research.

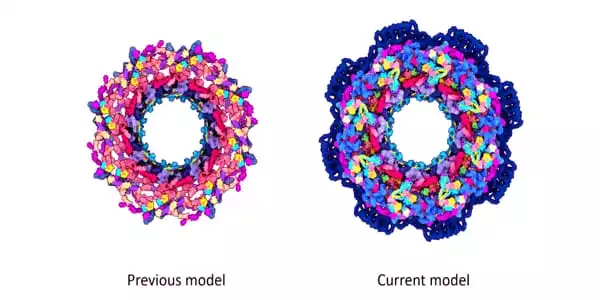

The association between temperature and a part of the birds’ DNA known as “telomeres” was the subject of our research on week-old nestlings.

Telomeres are DNA caps at the ends of chromosomes that serve as a buffer to protect cells from the consequences of energy generation and stress, among other things. The cell shuts off when the buffer erodes. The aging process accelerates as the number of these dormant cells increases over time.

During their early days of life, nestlings exposed to hot, dry circumstances have shorter telomeres. This shows that surviving heat stress may reduce the birds’ protective DNA buffer, causing them to age faster. Indeed, earlier study has shown that nestlings with shorter telomeres die younger and produce fewer progeny as a result.

Nestlings seemed to endure heat better when it was accompanied by rain, though we’re not sure why.

What this means in the context of global warming

Hot, dry weather is expected to become increasingly common in Australia as a result of climate change. As a result, we created a mathematical model to see if their impacts on nestling telomere length would be enough to induce population collapse.

Even at relatively low rates of warming, we discovered that the population might drop merely as a result of nesting telomere shortening. The arithmetic also indicated two possible “escape” strategies for preserving population viability.

For starters, the population may grow longer telomeres, providing a stronger buffer against premature aging. However, because we don’t know how telomeres evolve or if they can keep up with climate change, this is just speculation.

Alternatively, the birds’ breeding schedules might be altered so that nestlings are exposed to wetter weather more frequently. However, given the frequency of rainy days in the region is expected to decrease, and the birds already attempt to optimize nesting when it rains, this appears improbable.

Importantly, if global warming continues to rise, any remedies’ effectiveness will become increasingly improbable.

Heat-related hidden and delayed costs, such as those found in our study, might be subtle and difficult to identify. They are, nonetheless, critical when contemplating how climate change may influence biodiversity.

Because growing animals are more susceptible to heat and telomeres work similarly across species, our findings might be applied to a wide range of different birds and mammals. This needs to be confirmed by more study.

What’s next?

For parent birds, keeping cool is also costly. Birds, like humans, seek the shade and become less active in hot weather. They open their beaks to pant and extend their wings to cool off instead of sweating.

However, as a result of these behaviors, a parent bird has less time to forage, defend the nest, or feed offspring—all of which are necessary for the population to thrive. We’re looking at whether this makes the impacts of telomere shortening worse.

The next step in our investigation will be to take temperature readings inside and outside the nest. We’ll also look into whether females may choose cooler microsites for their young to assist them cope with climate change, and how this relates to habitat quality, management, and threats.

Finally, we hope that our findings will help to shape conservation plans that will ensure the survival of this iconic Australian species and others like it in the face of climate change.