If you are unfamiliar with centipedes, one thing you should know about them is that they are like hell. Fantastic, complex creatures sure, but a mobile ruler with poison and a mood does not make the moon a friend. As expert hunters, they really wake up every day and choose violence, killing prey up to 15 times their weight (TW, if you like rats, do not click this link). Their venom is so effective that some Venezuelan centipedes can catch and kill much larger flying bats than they kill.

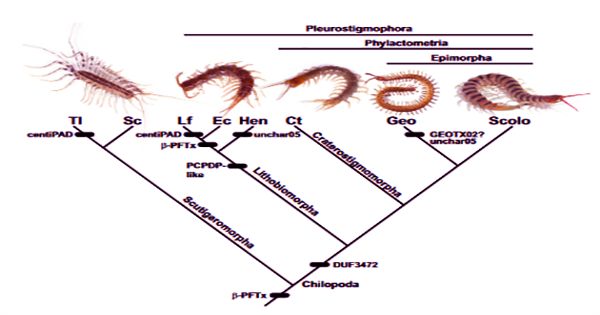

A new study published in the journal Nature Communications now reveals that something more interesting about centipede venom that is simply more effective than Dr. Ronald Jenner, an expert at the Natural History Museum in London, and Dr. from the University of Oslo and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. A genetic analysis of the toxin, led by a colleague of Dr Eivind Undheim, revealed for the first time that it contained weapons in the form of toxic proteins borrowed from bacteria and fungi.

The surprising discovery came as part of a larger study where Jenner and Undheim were looking to see if the protein in the centipede gene would have evolved anywhere in the tree of life outside the arthropods, a kind of fun critique of centipedes that centipedes sit firmly within. To be sure, they found evidence of several proteins of centimeter germs originating between bacteria and fungi, revealing their firearm as a cocktail of genetic information of completely unrelated species.

This type of interdisciplinary business occurs through an event called “horizontal gene transfer” and facilitates the movement of genetic material between distant organisms. This differs from vertical gene transfer, which is a more common movement of genetic material from ancestor to descendant. “This discovery is remarkable,” Jenner said in a statement emailed to IFLScience.

Although it seemed a bit late in the game that we had discovered such significant information about a poison that we had known for a while, when it was not dangerous to focus on the subject of toxic research, it was a species of centimeters low priority people have. This may have changed, now that it has finally published as a poster species for horizontal gene transfer. That said, we would still recommend giving these beauties spacious berths in the field.