The appearance of a mystery location in the South Atlantic where the geomagnetic field strength is quickly deteriorating has sparked suspicion that Earth is on the verge of reversing its magnetic polarity. Recent research, though, reveals that the present alterations aren’t exceptional and that a reversal may not be in the cards after all. The research was published in the journal PNAS.

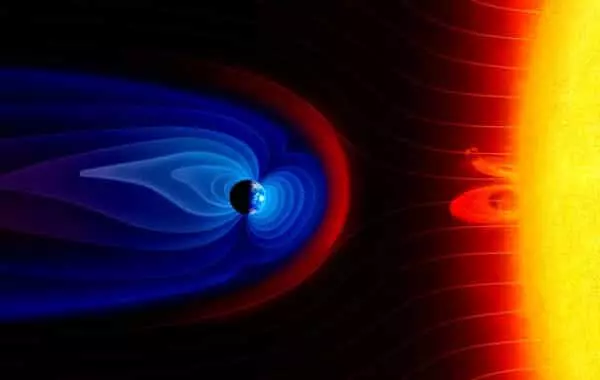

The magnetic field of the Earth works as an unseen screen against the life-threatening environment in space, as well as solar winds that would otherwise sweep the atmosphere away. However, the magnetic field is not stable, and polarity reversals occur at unpredictable intervals every 200,000 years on average. This implies the magnetic North and South poles are switched around.

The intensity of Earth’s magnetic field has declined by around 10% during the last 180 years. Simultaneously, in the South Atlantic, off the coast of South America, a region with an exceptionally weak magnetic field has grown. The South Atlantic Anomaly is a region where satellites have malfunctioned multiple times owing to exposure to highly charged particles from the sun. These events have sparked suspicion that we are on the verge of a polarity shift. However, according to a new study, this may not be the case. “We’ve studied changes in the Earth’s magnetic field over the last 9,000 years, and anomalies like the one in the South Atlantic are most likely periodic occurrences connected to comparable fluctuations in the Earth’s magnetic field strength,” says Andreas Nilsson, a geologist at Lund University.

The findings are based on examinations of charred archaeological artifacts, volcanic materials, and sediment drill cores, all of which include magnetic field information. Clay pots that have been cooked to above 580 degrees Celsius, hardened volcanic lava, and sediments deposited in lakes or the sea are examples of these. The items serve as time capsules, storing information about the previous magnetic field. The researchers were able to quantify these magnetizations and reconstruct the direction and strength of the magnetic field at specified locations and times using sophisticated instrumentation.

Andreas Nilsson explains, “We have created a novel modeling approach that integrates these indirect measurements from diverse time periods and locales into one worldwide reconstruction of the magnetic field over the last 9,000 years.”

Researchers can learn more about the fundamental mechanisms in the Earth’s core that create the magnetic field by looking at how it has evolved. By comparing actual and predicted fluctuations in the magnetic field, the new model may also be used to date archaeological and geological data. And, more reassuringly, it has led them to a conclusion about polarity reversal speculations:

“Based on parallels with the reconstructed anomalies, we anticipate that the South Atlantic Anomaly will most likely vanish within the next 300 years, and that Earth is not on the verge of a polarity shift,” Andreas Nilsson concludes.