It is critical to get out of a dangerous situation if you want to live. Animals must quickly learn a new habitat in order to pick the quickest path to safety. But how do they accomplish it without ever having been in a situation where they were threatened?

When mice are afraid, neuroscientists at UCL’s Sainsbury Wellcome Center investigated how they learn about their spatial surroundings and the behavioral methods they adopt to find the quickest way to a refuge.

The researchers reveal in a new study published today in Current Biology that mice learn the quickest way to escape after only 10 minutes of investigating the surroundings, and they don’t need any prior danger experience.

“Mice are trained to complete complicated mazes and given a lot of time to learn how to do so in many neuroscience research. Mice, on the other hand, do not have that luxury in nature; when threatened, they must flee to safety as swiftly as possible. The mystery is how mice learn so rapidly and without the benefit of trial and error “corresponding author on the study Tiago Branco, Group Leader at the Sainsbury Wellcome Center.

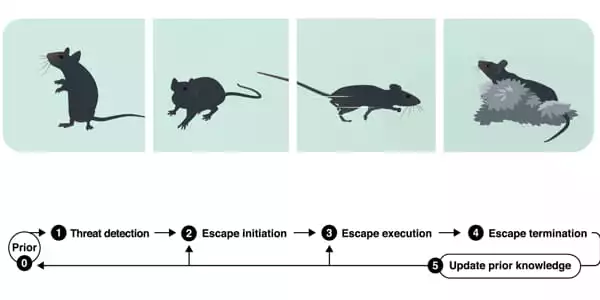

The SWC researchers conducted a series of behavioral studies in which mice were given a choice of two or three ways back to a shelter. The mice were scared by a loud sound or looming stimulus that simulated a predator, and the scientists then tracked their journey back to safety.

The neuroscientists first blocked the straight route to the refuge and discovered that the mice learned to utilize one of the alternate paths. The researchers next tested whether the mice could accurately pick between two pathways of varying lengths. Because the studies were conducted in the dark, the mice were unable to perceive the shortest path. However, the researchers discovered that mice prefer the shorter way, especially when the length differences between the two courses are greater.

The researchers looked at mice who were being threatened for the first time to see how they learned this and discovered that the inexperienced mice already preferred the shorter way. As a result, the mice must learn how to find the optimal escape path by natural exploration rather than having to encounter danger first. Furthermore, the mice discovered this after only ten minutes of exploration.

“Mice are preyed upon by a variety of animals, therefore knowing how to flee to safety is crucial for a mouse. When a mouse is placed in an unfamiliar area, its first concern is to map out the space and find out how to get to a safe location. This is part of the mouse’s natural repertoire of behavior and does not require explicit instruction “Tiago Branco expressed his thoughts.

Animals are supposed to learn through experiencing the value of something and mapping that value onto the spatial geometry. Mice, for example, would assign a lower value to the long road and learn to select the shorter path instead if they were regularly exposed to hazards and were stressed by traveling the long path back to safety.

The animals in this experiment, however, were not doing so. Instead, the mice felt that taking the shortest route to safety was the greatest option. This assumption is referred to as an inbuilt heuristic by the researchers. Mice have evolved a network of brain circuits that allow them to make these instinctive decisions following spontaneous exploration.

“Animals are excellent at learning about topics that are important to them. It’s vital to look at the behaviors that mice have evolved to undertake and the limits that they face in order to learn quickly and effectively in order to understand the mouse brain and the algorithms and neural circuits that enable learning “Tiago Branco said.

The researchers looked at three different computer models and questioned whether the artificial algorithms could do as well as the mice in the challenge. To investigate the algorithms, the researchers employed the brain to enable the mice to find the optimum escape path. They discovered that allowing the artificial mouse to explore for an extended period of time improved the performance of all three methods. The genuine mouse, on the other hand, had only 10 minutes to investigate.

So the researchers provided the artificial mouse with the real mouse’s trajectories and discovered that the simplest conceivable method, dubbed model-free, could not learn to take the shortest path. The two more complicated models, known as model-based, were capable of learning the ideal escape path, although they were only right about half the time. This provides the researchers with some insight into what the brain requires for the mice to choose the best escape path. The researchers’ next steps will be to investigate how this works in the brain and how mice transfer value to activities in this natural scenario. This question is a small component of the greater puzzle of how animals decide what actions to take depending on their expectations of what would be beneficial in the short or long run. Neuroscientists seek to obtain an understanding of this type of value mapping in an action behavior in order to gain insight into the types of algorithms that the brain may be utilizing to perform quick learning.