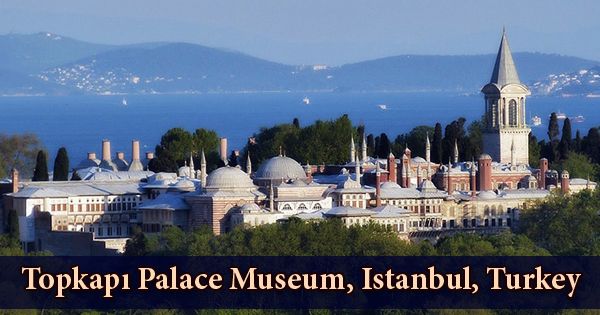

The Topkapı Palace (Turkish: Topkapı Sarayı; Ottoman Turkish: طوپقپو سرايى, Ṭopḳapu Sarāyı; meaning –Cannon Gate Palace), a museum in Istanbul, Turkey, which displays the Ottoman Empire’s imperial collections and houses in its library an extensive collection of books and manuscripts. Topkapi Palace is the focus of more vivid stories than are put together by most museums in the world. It served as the main residence and administrative headquarters of the Ottoman sultans in the 15th and 16th centuries. In 1924, a year after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, it opened as a museum. Not only for its architecture and collections but also for the history and culture of the Ottoman Empire that it remembers, the Topkapı Palace Museum is notable.

The Topkapi Palace, which also means Cannon Gate Palace, once operated during the 15th century as the main residence and administrative headquarters of the Ottoman Empire’s influential sultans. Construction began in 1459, six years after the conquest of Constantinople, under the order of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror. To differentiate it from the Old Palace (Eski Saray or Sarây-ı Atîk-i Âmire) in Beyazıt Square, Topkapı was originally named the “New Palace” (Yeni Saray or Saray-ı Cedîd-i Âmire). In the 19th century, it was given the name Topkapı, meaning Cannon Gate.

Hagia Eirene, Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul.

During the Ottoman Empire’s 600-year reign, starting with Mehmed II, about 30 sultans ruled from the Topkapi Palace for almost four centuries. In the late 1450s, some years after capturing Constantinople (Istanbul), the capital of the Byzantine Empire, in 1453, he ordered the building of a palace. Medmed took up residence in 1478, and three years later, after his death, successive sultans often restored and enlarged the palace, resulting in the palace’s medley of evolving styles and decorations of Islamic, Ottoman, and European architecture.

Topkapi Palace is situated on the 700,000 square meter area between the Golden Horn and Bosphorus in the Istanbul peninsula, and the Topkapi Palace was walled away from the city to provide the requisite protection and privacy. Over the years, with significant repairs after the 1509 earthquake and the 1665 fire, the complex expanded. Four main courtyards and several smaller buildings make up the palace complex. 1,000-4,000 inhabitants were housed in the massive Topkapı Building, including up to 300 in the harem. In the harem, female members of the Sultan’s family stayed, and in the Imperial Council house, leading state officials, including the Grand Vizier, held meetings.

Tower of Justice, Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul

After the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey on 3rd April 1924, Topkapi Palace began to be used as a museum. Another important aspect of Topkapi Palace was that it was the Turkish Republic’s first museum. The palace complex has hundreds of rooms and chambers, but as of 2020, only the most important ones are open to the public, including the Ottoman Imperial Harem and the treasury, called hazine, where the Diamond of the Spoonmaker and the Topkapi Dagger are on display. Ottoman clothing, arms, armor, miniatures, religious relics, and illuminated manuscripts, such as the Topkapi manuscript, are also included in the museum collection.

Topkapi Palace is always a crowded and fascinating attraction point that draws tourists from all over the world and has a great interest and effect on tourists visiting it, Topkapi Palace is also a popular point for visitors who live in Turkey and visit Istanbul, as well as for those who want to see and discover the history of the Ottoman Empire and more about the history of the Ottoman Empire; Since there are so many significant collections, architectural buildings and nearly 300,000 archive documents in Topkapi Palace. The Topkapi Palace is part of the Istanbul Historic Areas, a group of Istanbul sites that UNESCO listed as a World Heritage Site in 1985.

Gate of Salutation, Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul

The first courtyard is the largest and only public courtyard (sometimes called the Outer Courtyard). Through the Imperial Gate, any unarmed individual could enter during the reign of the Ottoman Empire. Originally dated from 1478, this huge gate is now paved in 19th-century marble. The central arch leads to a high-domed passage; the framework at the top is decorated by gilded Ottoman calligraphy, with verses from the Qur’an and sultans’ tughras. The open space of the courtyard made it suitable for ceremonies and processions, and it was probably the most vibrant of the squares in the palace.

The Middle Gate (Ortakapı or Bab-üs Selâm) led to the Second Court of the palace, used for the business of running the empire. Only the sultan and the legitimate sultan (mother of the sultan) were permitted on horseback through the Middle Gate in Ottoman times. Everybody else, the Grand Vizier included, had to dismount. The Tower of Justice is one of the most hilarious things to concentrate on after passing the second courtyard. There is also the Royal Divan that was used to make decisions about and around the empire. The curious point is that, instead of attending and chairing the sessions, the Sultan did not chair these meetings, he only listened behind the gold curtain at the back of the room. If the Sultans did not support the decision, they would close the curtain or tap on the screen to let them know that they disagreed with the decision they had made.

The Library of Sultan Ahmed III, Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul

The second courtyard was also home to the kitchens and confectionaries of the palace, which now houses the collection of imperial porcelain, as well as the External Treasury, which displays imperial arms. The gate of Felicity at the end of the courtyard is another point of Topkapi Palace, hosting the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire while the ceremonial occasions were displayed, the Sultans sat down there and observed the ceremonial occasions. There is a small stone in front of this gate that was used to show the Sancaki Serif, or Prophet Muhammad’s standard, before the army and the Sultans went to battle against their own enemies.

Like other items in the Museum of the Topkapi Palace, the pieces in both collections were either created by the Sultan’s workshops, bought at markets, collected as gifts from foreign dignitaries, or gathered from conquered populations. Objects in the collection of porcelain demonstrate the empire’s vast scope, with items acquired from China and Japan. Celadon from China was particularly valued as tableware because of the belief that if the food served inside it was poisoned a superstition that points to the constant fear of assassination of the Ottoman sultans, it would change color.

In the typical configuration of an Ottoman building, with baths and a mosque, as well as recreational rooms such as a pipe room, the dormitories are designed around the main courtyard. Many pious foundation inscriptions can be found on the outside and inside of the complex regarding the different duties and maintenance of the quarters. The quarters are made of red and green painted wood, in contrast to the rest of the palace. Beneath the Tower of Justice on the western side of the Second Court is the gateway to the Harem. When rooms are closed for renovation or stabilization, the visitor route through the Harem changes, so some of the areas listed here may not be available during visits by visitors/tourists.

Interior of the Twin Pavilions, Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul

Opposite the Imperial Divan, delicious scents of beautiful Ottoman food spread, these foods ranged from all kinds of desserts to meals cooked by very talented Ottoman Empire cookers. These meals were cooked on a regular basis for around 5,000 palace employees. After the 1574 fire that destroyed the kitchens, the architect of the court, Mimar Sinan, restored them. Two rows of 20 large chimneys form the reconstructed kitchens; Mimar Sinan has added these chimneys. In addition to displaying kitchen utensils, the buildings today contain a collection of silver gifts, as well as a large porcelain collection.

The collection of the Topkapi Palace contains rare manuscripts, illustrated books, and early Quran copies, all of which can be looked over in the reading room by scholars. Another part of Topkapi Palace is the Harem, probably one of the most mysterious parts of palaces where harems are the past because all kinds of tricks and plans have been made here to gain power and be the Sultans’ one of the most loved woman. The harem was constantly renovated, like the rest of the palace, and grew according to need. A very mazelike structure and several types of architecture are the results. The Harem was a place, as common wisdom would have it, where the sultan could indulge in debauchery at will. These were the imperial family quarters in a more prosaic reality, and every aspect of Harem’s life was regulated by custom, duty, and ceremony. The word ‘harem’ means ‘forbidden’ or ‘private’ literally.

Abdülmecid I transferred the imperial court from Topkapı Palace to the newly built Dolmabahçe Palace in the mid-19th century. Some of the Topkapi Palace buildings have maintained their functions, and others have fallen into disrepair. The Fourth Courtyard (IV. Avlu), also known as the Imperial Sofa (Sofa-ı Hümâyûn), was the sultan and his family’s innermost private refuge, containing a variety of pavilions, kiosks (köşk), gardens and terraces. It was originally a part of the Third Courtyard, but to better differentiate it, recent scholars have identified it as more distinct. Many of the buildings were restored when the palace became a museum in 1924, and parts of the complex are frequently closed off for this reason. More than three million visitors a year come to the museum.

Information Sources: