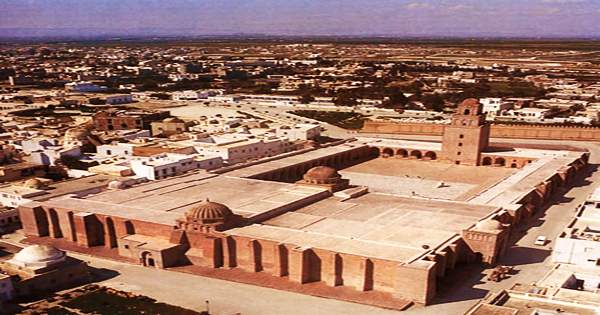

In the historic walled district of Medina, between Rue de la Kasbah and Rue el Farabi, the Great Mosque of Kairouan (Arabic: جامع القيروان الأكبر), also known as the Mosque of Uqba (جامع عقبة بن نافع), is located. It is a mosque located in Kairouan, Tunisia, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and is one of North Africa’s most impressive and largest Islamic monuments. The original mosque was totally demolished, and in the 9th century, much of what stands today was constructed by the Aghlabids. Founded in the year 50 AH (670AD/CE) by the Arab general Uqba ibn Nafi at the founding of the city of Kairouan, the mosque occupies an area of more than 9,000 square meters (97,000 sq ft). It is one of the oldest places of worship in the Islamic world, and a model in the Maghreb for all subsequent mosques. A hypostyle prayer hall, a marble-paved courtyard, and a square minaret are part of its perimeter, approximately 405 meters (1,329 ft).

The mosque, as it stands today, was constructed between 817 and 838 by the Aghlabid governor of Kairouan, Ziyadat Allah. The building was erected on the site of an older mosque, originally founded at the time of the 670 AD Arab conquest of Byzantine North Africa by Uqba ibn Nafi. About 690, shortly after its completion, the mosque was demolished by the Berbers, originally led by Kusaila, during the occupation of Kairouan. The Mosque of Uqba, in addition to its theological prestige, is one of the masterpieces of Islamic architecture, notable for the first Islamic use of the horseshoe arch, among other items. The minaret is the oldest in the Maghreb, and there are 414 pillars supporting horseshoe arches in its impressive prayer hall; non-Muslims can peer into it from the inner courtyard, but can’t enter.

The popularity of the Uqba Mosque and the other holy sites in Kairouan has helped the city to develop and expand. The mosque is situated in the intramural district of Houmat al-Jami, north-east of the medina of Kairouan (literally “area of the Great Mosque”). Although the current mosque retains virtually no trace of the original seventh century building, it is still generally referred to as “Mosque of Sidi Uqba”, or, “Mosque of Uqba Ibn Nafi.” Historically, great importance has been given to it as the first mosque in the first city of Islam in the West. In 703, the Ghassanid General Hasan ibn al-Nu’man rebuilt the mosque. Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, Umayyad Caliph in Damascus, commissioned his governor Bishr ibn Safwan to carry out construction work in the region, including the renovation and expansion of the mosque around the years 724-728 AD, with the gradual increase of the population of Kairouan and the consequent increase in the number of faithful.

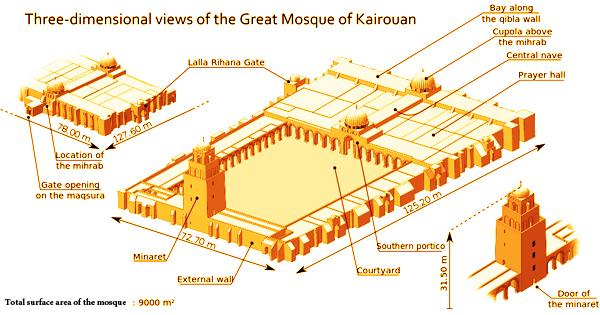

The building is a massive quadrilateral that is slightly irregular, covering some 9,000 m2. It is longer on the east side (127.60 meters) than on the west side (125.20 meters), and shorter on the north side (72.70 meters) than on the south side (78 metres). The principal minaret is north-centered. The exterior has a traditionally unadorned Aghlabid style, with its buttressed walls. When you walk into the vast, marble-paved courtyard, enclosed by an arched colonnade, impressions shift. The courtyard was built to capture water, and the paving slopes to an intricately decorated central drainage hole that delivers the rainwater collected to the cisterns below in the 9th century. The decorations have been crafted to filter the water’s dust. Both of the two wells’ marble rims have deep rope-grooves worn by millennia of water drawing up from the depths.

A number of important additions, including the inclusion of a nearby wide courtyard and the building of a pool now known as the Old Cistern, were made between 703 and 816. (Al-Majal al-Qadim). This time is most frequently attributed to the building of the minaret, although some scholars consider it to be part of the later work of Ziyadat Allah. The next major reconstruction came in 836, when Ziyadat Allah completely rebuilt the sanctuary, including the dome above the mihrab. From the outside, with its 1.90 meters thick massive ocher walls, the Great Mosque of Kairouan is a fortress-like structure, a composite of well-worked stones with intervening rubble stone courses and baked bricks. In 856, by adding a double-arcaded portico to the sanctuary with a domed entry bay, Abu Ibrahim Ahmed started the work that would bring the mosque to its twentieth-century configuration. The portico enveloping the interior of the courtyard is also often assigned to this period; however, some texts cite Ibrahim Ibn Ahmad (874-902) as its builder.

The three-tiered minaret in the square occupies the northwestern end of the courtyard. In AD 728, the lowest level was built. Note the two Roman slabs at its base (one upside down) bearing Latin inscriptions. On either side, the corner towers measuring 4.25 metres are supported by strong projecting supports. Structurally, the buttressed towers provided stability to the entire mosque given the soft grounds prone to compaction. At the southern end of the courtyard is the prayer hall. The massive, studded wooden doors here date from 1829; especially fine are the carved panels above them. The pillars were, like those of the colonnade, originally Roman or Byzantine, salvaged from Carthage and Hadrumètum (Sousse), and no two are the same.

The complex measures about 70 by 125 meters and is oriented northwest-southeast, being slightly irregular in shape. In 836, the mosque was rebuilt again by Emir Ziyadat Allah I: this is when the structure acquired its present appearance, at least in its entirety. At the same time, the mihrab’s ribbed dome was raised on squinches. The present state of the mosque can be traced back to the Aghlabid era, except for some partial restorations and a few later additions made in 1025 during the Zirid period, 1248 and 1293-1294 under the reign of the Hafsids, 1618 at the time of the Muradid beys, and in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, no feature is older than the ninth century except the mihrab.

(The Great Mosque of Kairouan)

Six portals, facing northeast and southwest, join the courtyard. The prayer hall, as well as two sheltered doorways from the foot, is entered from the courtyard. At the far end of the main prayer hall, between two red marble columns, you can just make out the precious 9th-century tiles behind the mihrab (niche showing the path of Mecca). For the richly decorated minbar (pulpit) next to them, the tiles were imported from Baghdad along with the wood. The ribbed dome in front of the mihrab has epigraphic and floral decoration and is widely known as a masterpiece of the Aghlabid. With the exception of two domes, one above the mihrab (dating from 836) and one above the portico’s entrance bay, the roof is level (reconstructed in the nineteenth century after its 856 form). The two-bay-deep arcade flanking the courtyard is a later addition, and consists of horseshoe arches resting on rectangular pillars fronted by twin columns.

The Great Mosque of Kairouan has been the subject of numerous accounts by Arab historians and geographers in the Middle Ages for many centuries after its establishment. The stories primarily concern the various phases of the sanctuary’s building and expansion and the successive contributions of several princes to the interior decoration (mihrab, minbar, ceilings, etc.). Abu Ibrahim Ahmed designed the present mihrab, based on the qibla wall. Some scholars claim that Uqba Ibn Nafi’s original mihrab can be seen through the open-work marble of today’s mihrab. Set in a horseshoe-shaped niche, it is surmounted by a semi-dome of curved wooden planks attached to a supporting structure. A gold pigment against the dark backdrop of the wooden half dome is painted in intricate floral designs. In four horizontal rows, twenty-eight white marble panels line the polyhedral interior of the niche of the mihrab. Some of the Western travelers, poets and authors who visited Kairouan sometimes leave their experiences and testimonies tinged with emotion or appreciation in the mosque. On one side, the wooden framework of the maqsura is fixed to the qibla wall and is connected to the arcade pillars with thin iron bands at the inner corners. A door (Bab al-Imam) on the qibla wall and a pair of double doors opening to the sanctuary are accessed via it. Today, the enclosure of Kairouan’s Great Mosque is pierced by nine gates (six openings to the courtyard, two openings to the prayer hall and a ninth opening to the maqsura hall), some of which, such as Bab Al-Ma (water gate) located on the western façade, are followed by prominent porches flanked by buttresses and surmounted by square tholobate-based ribbed domes carrying squinches with three vaults.

Information Sources: