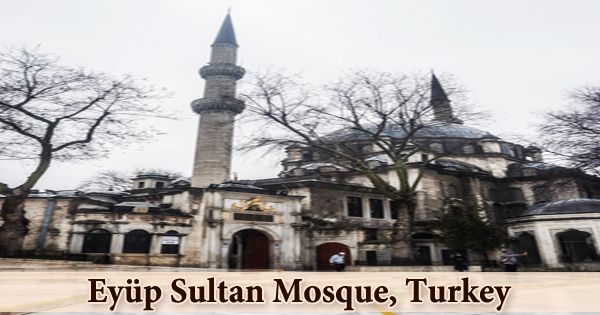

The Eyüp Sultan Mosque (Turkish: Eyüp Sultan Camii) is a very unique and holy mosque for the Islamic world; it is located in the district of Eyüp on Istanbul’s European side, near the Golden Horn, and outside the walls of Constantinople. The current structure dates from the early 19th century. It was the first mosque built by the Ottoman Turks after the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, and it was completed in 1458. The mausoleum marks the location where Abu Ayyub al-Ansari (Ebu Eyüp el-Ensari), the Islamic prophet Muhammad’s standard-bearer and companion, is said to have been buried. Sultan Mehmet II intended to construct a grand tomb to mark the site of Eyüp’s grave, which was discovered outside the city walls shortly after the Conquest. The Ottoman princes came to the mosque complex he commissioned for the Turkish equivalent of a coronation ceremony: the girding of the Sword of Osman to indicate their authority and title as padişah (king of kings) or sultan. The Eyup Sultan Mosque’s decorated dome, which measures 17.5m in diameter and is supported by two half domes, has an elegant architecture. Eyüp’s tomb is possibly more interesting than the mosque itself. It’s open Tuesday through Sunday from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., and it’s covered in tile panels from various ages, creating a lovely, if overwhelming, effect. By the end of the 18th century, the mosque had fallen into disrepair, possibly as a result of earthquake damage, and Sultan Selim III ordered the entire building, except the minarets, to be demolished and rebuilt in 1798. In the year 1800, this project was completed. Mahmud II reconstructed the eastern minaret in the original style in 1822.

A fun leafy area to walk through is the Eyüp Cemetery, which leads up the hill from the mosque. The Ottoman princes came to the mosque complex he commissioned for the Turkish equivalent of a coronation ceremony: the girding of the Sword of Osman to indicate their authority and title as padişah (king of kings) or sultan. Eyüp Sultan is thought to have died in the 670s during the first Arab siege of Constantinople. Muslims hold his tomb in high regard. The mausoleum is located on the north side of a courtyard, directly across from the mosque’s main prayer hall entrance. Thousands of Muslims flock to the mausoleum on Fridays, which are holy days in Islam. Around the mosque and mausoleum, old trees, flocks of pigeons, praying believers, and visiting crowds create a magical and colorful atmosphere. Tiles from various periods cover the walls of the mausoleum in the courtyard. Turkey’s oldest and most sacred mosque is the Eyüp Sultan Mosque. Its style was altered several times by the Ottomans, who designed it in accordance with their own style of architecture at the time. Mimar Sinan, a well-known Ottoman architect, designed the Eyüp Sultan Mosque. Mimar Sinan was the son of either Greek or Armenian Christian parents. According to historical accounts, this district was also a holy site in Byzantine times, where people came to visit a saint’s grave and pray for rain during droughts. A variety of contrasting panels of Iznik tiles can be found on the mausoleum’s wall facing the mosque. They are from various times and were brought together during the mosque’s restoration in 1798-1799. Iznik tiles are also used to cover the walls of the mausoleum’s vestibule. They date from about 1580 and have the distinctive sealing-wax red slip. Similar tiles to those found in the vestibule can be found in a number of museums outside of Turkey; they likely once adorned the walls of the baths’ now-demolished entrance hall (camekân). The baroque mosque replaces the original, which was demolished in the 1766 earthquake, but the main draw is the türbe, a holy burial site that attracts crowds of pilgrims waiting in line to see the contents of the solid silver sarcophagus or to meditate in prayer. A panel of three blue and turquoise Iznik tiles, dated from about 1550, is housed in the British Museum and is identical to some of the ones that now adorn the shrine’s exterior wall.