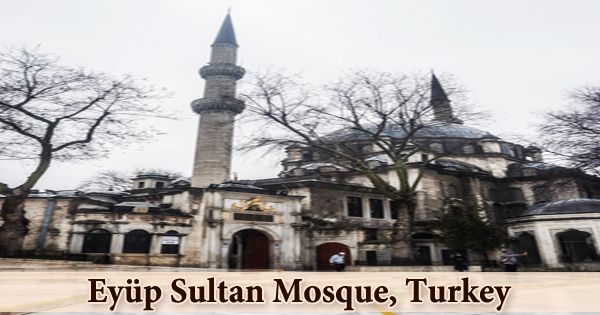

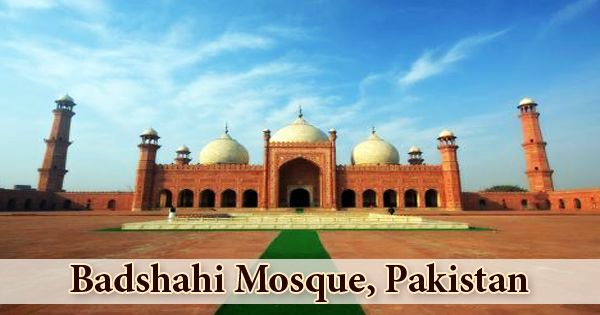

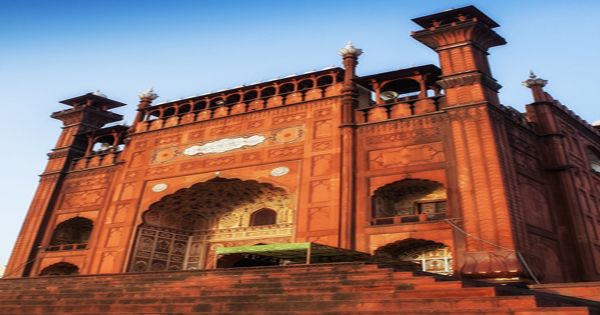

One of the few important architectural monuments constructed during the long rule of Emperor Aurangzeb from 1658 to 1707 is the Badshahi Mosque (Punjabi and Urdu: بادشاہی مسجد, or “Imperial Mosque“). It is the mosque of the Mughal period in Lahore, the capital Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan. It is currently the world’s fifth-largest mosque and was undeniably the world’s largest mosque from 1673 to 1986 when Islamabad’s Faisal Mosque was completed. The mosque is situated west of Lahore Fort on the outskirts of Lahore’s Walled City and is widely regarded as one of the most iconic landmarks in Lahore. Although it was constructed in a time of relative decline late in the Mughal era, its beauty, elegance, and size, like no other monument in Lahore, epitomize Mughal cultural achievement. Replete with immense walls, four tapering red sandstone minarets, three vast marble domes, and an open courtyard that was said to accommodate up to 100,000 people, it was destroyed and later rebuilt by the British.

Night view of Badshahi Mosque, Pakistan

The mosque remains the largest on the Indian subcontinent, considered one of the last great monuments of the Mughal period. Emperor Aurangzeb built the Badshahi Mosque in 1671, with the building of the mosque lasting for two years until 1673. The mosque, with an exterior decorated with carved red sandstone with marble inlay, is an important example of Mughal architecture. Under the guidance of Muzaffar Hussain (Fida’i Khan Koka), the brother-in-law of Aurangzeb and the governor of Lahore, construction of the mosque began in 1671. It was originally intended to safeguard a strand of the hair of the Prophet as a reliquary. Its great scale is inspired by the Delhi Jama Mosque, designed by the father of Aurangzeb, Shah Jahan.

It remains the largest mosque of the Mughal period and is Pakistan’s second-largest mosque. The mosque was used as a garrison by the Sikh Empire and the British Empire after the collapse of the Mughal Empire and is now one of Pakistan’s most iconic sights. A square measuring 170 meters on either side is basically the plan for the Badshahi Mosque. Since the north end of the mosque was built along the edge of the Ravi River, a north gate like the one used in the Jama Mosque could not be placed, and a south gate was also not constructed to preserve the overall symmetry. The prayer hall inside the courtyard features four minarets that echo the four minarets at each corner of the perimeter of the mosque in miniature.

The Badshahi Mosque features a monumental gateway that faces the Hazuri Bagh quadrangle and Lahore Fort.

The mosque’s full name “Masjid Abul Zafar Muhy-ud-Din Mohammad Alamgir Badshah Ghazi” is written in inlaid marble above the vaulted entrance. It is said that the rooms above the entrance gatehouse the hair of the Prophet Mohammed and other artifacts. When it is illuminated in the evening, the mosque looks lovely. The mosque is also located next to the Roshnai Gate, one of the original thirteen gates of Lahore, which is located to the southern side of the Hazuri Bagh. The Tomb of Muhammad Iqbal, a poet widely revered in Pakistan as the founder of the Pakistan Movement that led to the development of Pakistan as a homeland for the Muslims of British India, lies near the entrance of the mosque.

The mosque stands at each corner in a walled enclosure with high minarets, all constructed on a high plinth that raises it above the town and fort. Each corner of the mosque itself is marked by another set of minarets. In the imperial view, the importance of the mosque was such that it was built just a few hundred meters west of the Fort of Lahore. Added to the fort was a special gate facing the mosque and called the Alamgiri gate. The field between the future Hazuri Bagh garden was used as a parade ground where his troops and courtiers would be inspected by Aurangzeb. Since the latter was built on a six-meter plinth to help avoid flooding, the Hazuri Bagh seems to be at a lower level than the mosque. The tomb of Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan, who is credited with playing a major role in maintaining and rebuilding the mosque, is also located near the mosque’s entrance.

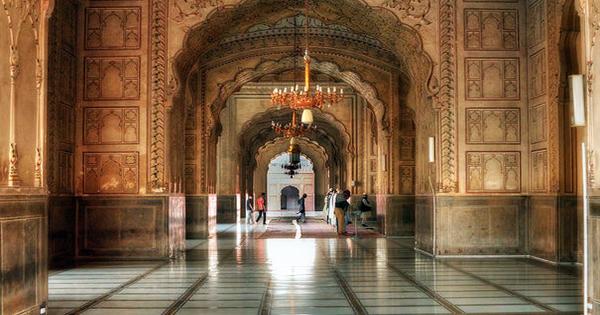

Interior view of Badshahi Mosque

The elevated central Iran façade is arcaded. Completing the composition are three white marble double-domes, the central one significantly larger than the others. In 1818, in the Hazuri Bagh facing the mosque, known as the Hazuri Bagh Baradari, Maharaja Ranjit Singh constructed a marble building which he used as his official Royal Court of Audience. The Sikhs from other monuments in Lahore may have plundered marble slabs for the baradari. He noted that the mosque was used as an exercise ground for the Sipahi infantry when William Moorcroft of England visited Lahore in 1820. Twenty years later, a moderate earthquake reached the shore and the delicate marble turrets at the top of each minaret collapsed. The open turrets were used a year later as gun locations when Ranjit Singh’s son, Sher Singh, occupied the mosque during the Sikh civil war to bomb Lahore Fort.

In 1849 the British took possession of Lahore from the Sikh Empire. The mosque and the surrounding fort continued to be used as a military garrison throughout the British Raj. It was not until 1852 that the British set up the Badshahi Mosque Authority to oversee the mosque’s reconstruction so that as a place of worship it could be restored to Muslims. It was not until 1939, although repairs were carried out, that substantial repairs began under the supervision of architect Nawab Zen Yar Jang Bahadur. Up until 1960, the repairs proceeded and were completed at a cost of 4.8 million rupees.

When hardline mullahs (Muslim religious leaders) protested at the visit of the late Princess of Wales in 1991, the mosque captured international headlines; her skirt was deemed too short and the mosque director was blamed for providing (the then) HRH, a non-Muslim, with a copy of the Quran and allowing her to dress immodestly in the sacred precincts. The case went to court and ended by asking the litigating mullahs to avoid wasting the time of the judge. The Mosque of Badshahi was tentatively identified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. In 2000, an inlay of marble was repaired in the main hall of prayer. Using red sandstone imported from the original Mughal source near Jaipur, in the Indian state of Rajasthan, replacement work on the red sandstone tiles on the large mosque courtyard began in 2008.

The mosque’s interior is decorated in painted plaster relief work with intricate floral and cartouche motifs, as well as with white marble inlay. An enormous sandstone paved courtyard stretches over an area of 276,000 square feet after passing through the massive gate, and which can accommodate 100,000 worshipers while acting as an Idgah. Single-aisled arcades enclose the courtyard. The chamber of prayer has a central arched niche flanking it with five niches that are around one-third the size of the central niche. There are three marble domes in the mosque, the largest of which is in the middle of the mosque and is flanked by two smaller domes.

Full view of Badshahi Mosque

The Tomb of Allama Mohammed Iqbal stands in the courtyard, a modest monument in red sandstone to the philosopher-poet who first postulated the concept of an independent Pakistan in the 1930s. The mosque’s interior and exterior are decorated with intricate white marble carved from a floral pattern typical to the architecture of Mughal art. The carvings at the Badshahi Mosque are considered to be special pieces of Mughal architecture that are fine and unsurpassed. On either side of the main hall, the chambers contain rooms used for religious instruction. In the prayer hall, the mosque can host 10,000 worshippers.

Information Sources: